0

0

952

By Jeff Rittener, Vice President, Global Trade

and Clifton Roberts, Director, Cloud Policy

Jeff Rittener, Vice President, Global Trade

Jeff Rittener, Vice President, Global TradeGrowth in emerging tech and increased national security checks made 2018 a year of policy-related activities regarding new export controls for certain new technologies, including artificial intelligence (AI). First, on August 13, 2018, the Export Control Reform Act of 2018 (ECRA) was signed into law. Under this act, the US Department of Commerce (USDC) was issued the authority to establish export controls on “emerging and foundational technologies” under the framework of the Commerce Control List.[1]

Clifton Roberts, Director, Cloud Policy

Clifton Roberts, Director, Cloud PolicySubsequently, on November 19, 2018, the Bureau of Industry and Security (BIS), an arm of the US Dept. of Commerce, published an advance notice of Proposed Rulemaking (ANPRM) seeking input on the criteria to be used by BIS to define emerging technologies for the purpose of establishing export controls. The goal of the advance notice was to elicit public input regarding potential updates to the control lists “without impairing national security or hampering the ability of the U.S. commercial sector to keep pace” with advances in emerging technology. Intel responded to the notice and took the opportunity to shape these future export regulations by responding to the BIS’ ANPRM in January of 2019, calling attention to the reality that when a technology is not fully developed, proposed controls could slow technology development, limit development resources, reduce market participation and limit opportunities to collaborate on tech development.

In its notice, BIS described the following broad categories of technology which it was studying and for which it is seeking advice:

|

|

While cloud and internet-related technology trade groups like the Internet Association asked the US Dept. of Commerce to “tread carefully when imposing export controls on new technologies,” arguing that overbroad regulations “could drive startups and innovators overseas,” Intel responded systematically, with specific guidance in the following five areas:

- Definition:How to define an “emerging” technology,

- Criteria:How to determine if a technology enhances/threatens national security,

- Sources: Sources for identifying technology important to US national security,

- Status: Phase of development these technologies are in, and

- Effect: Impact of controls on these technologies.

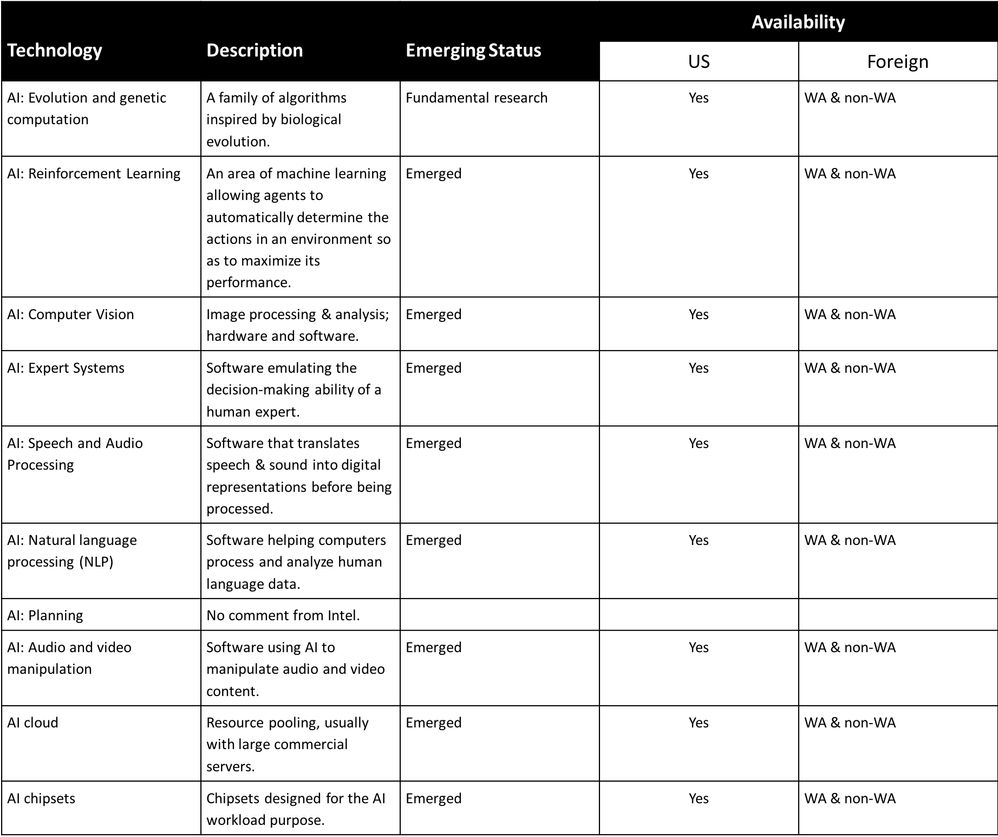

Noteworthy was the guidance for the “Status” area, and Intel’s assignment of Artificial Intelligence (AI) related technologies as “emerging technologies.” (See Table below.)

Intel concluded that when a technology is not properly developed and/or not yet fully “emerged,” BIS’s proposed controls can, and may, (a) slow the technology development, (b) limit development resources, (c) reduce market participation, and (d) limit collaborative opportunities, with the following details:

- Slow development process– Export controls add steps to the development process, i.e., through deemed export licenses for employees. Obtaining such licenses add processing time and delay or restrict development. One outcome of slow development processes could be less competitive U.S. products arriving late to the market.

- Limit development resources– Export controls may limit the ability of U.S. companies to hire the world’s most qualified engineers. The majority of STEM PhD graduates from U.S. universities are non-U.S. persons.[2]

- Reduce market participation– Certain U.S. companies may choose not to develop a technology due to the added burden of export controls.

- Limit collaborative opportunities– Export controls may limit the ability to partner with foreign companies to innovate together and further technology development.

Intel’s AI vision is to power the AI transformation by building the world’s best AI computing platform(s). To cultivate this transformation, we support public policy positions and legislative and regulatory initiatives that are comprehensive and technology neutral. Intel appreciates the opportunity to comment on the ANPRM and looks forward to working with BIS on the policy and regulatory steps identified in the Export Reform Control Act of 2018 in order to amend the Export Administration Regulations to better reflect technological innovation.

[1]Bureau of Industry and Security, Commerce. (2016). Commerce Control List.Retrieved from Bureau of Industry and Security Website: https://www.bis.doc.gov/index.php/regulations/commerce-control-list-ccl

[2]National Foundation for American Policy Brief, October 2017. “The importance of International Students to American Science and Engineering.” http://nfap.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/The-Importance-of-International-Students.NFAP-Policy-Brief.October-20171.pdf

You must be a registered user to add a comment. If you've already registered, sign in. Otherwise, register and sign in.